Drama for a Diasporic People

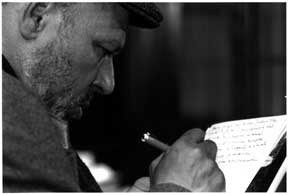

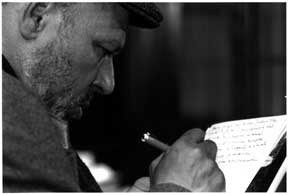

August Wilson illuminates a shared heritage on stage

by Sarah Hood

When people talk about playwright August Wilson, you know that eventually the word griot is going to pop up. Like the traditional West African holders of that title, Wilson is a keeper of the historical record, a documenter of social change, a poet. For the past 20 years, the two-time Pulitzer Award-winner has been telling the story of black America through an ongoing 10-play cycle, each play covering a decade of the 20th century.

Wilson speaks to the need to create a specifically African-American drama. "There's simply an African people who are in America; nonetheless, they are an African people," he says. "If you take Death of A Salesman and you try to present that play with an all-black cast, that's not the way that problem would have been dealt with in a black household."

Wilson first soared into the public eye with Ma Rainey's Black Bottom in 1984. Set in the 1920s, it imagines the details of a real recording session by blues great Ma Rainey, revealing a black community struggling to establish itself in the inhospitable climate of the white business world. While Ma herself has attained some clout - which she wields with uneven results - a younger musician, Levee, strives to get ahead with his own style, a new kind of music that will eventually take hold, although maybe not soon enough to help him.

Like many of Wilson's scripts, Ma Rainey premiered at the Yale Repertory Theatre, then went to Broadway, winning a New York Drama Critics Circle Award, and, later, an L.A. Drama Critics Circle Award, as well as a Grammy for Best Cast Album. (Toronto's Mercury Theatre produced the show at Theatre Passe Muraille in 1989; the cast included Joe Sealy, Doug Innis and Marium Carvell, with local jazz diva Jackie Richardson well cast in the title role.)

Wilson's second full-length play, Fences, (1988) won him his first Pulitzer, as well as a string of other honours literally too long to mention. With James Earl Jones in the lead role of Troy Maxson, Fences jumped to the America of 1957, when the impetuous momentum of the '60s was only beginning to stir. Baseball is a central metaphor, and Maxson fends off death by sheer force of will like a "fast ball on the outside corner." Fences also explores what is to be a critical theme in all the plays, the dynamics of the father-son relationship, for how can a people move forward if each generation cannot help the next to realize its own dreams?

Next in the series were Joe Turner's Come and Gone (1988); The Piano Lesson (1990); the jubilant Two Trains Running (1992), Seven Guitars (1996), Jitney (2000, about Pittsburgh cabmen) and King Hedley II (2001). Although performers of the stature of Jones, Goldberg, Larry Fishburne and Samuel L. Jackson have originated roles in Wilson's work, none of the plays really contain "star" parts. They are all ensemble pieces, because they concern the lives of communities as much as those of individuals. Throughout the various settings and time periods, the characters question over and over again how to build a family, an economy, and, above all, a sense of self worth.

Another consistent motif is the presence of the ancestors, as well as Death himself, as agents in the drama. In Wilson's work, the spirit world and the physical plane are very much connected. "I think they intersect," he says. "They certainly do within the black community. If I go back to Africa, the ancestors can certainly interfere in everyday life."

They play an especially important part in Wilson's transcendent 1990 script The Piano Lesson, which won him his second Pulitzer Prize, as well as an American Theatre Critics Award, the New York Drama Critics Circle Award and the Drama Desk Award. Toronto's Obsidian Theatre, Canada's professional black repertory company, is presenting The Piano Lesson as its second full production to date (after the highly lauded Adventures of a Black Girl in Search of God by local author Djanet Sears). It's only the second chance - ever - for Toronto audiences to see one of Wilson's plays professionally performed. They play an especially important part in Wilson's transcendent 1990 script The Piano Lesson, which won him his second Pulitzer Prize, as well as an American Theatre Critics Award, the New York Drama Critics Circle Award and the Drama Desk Award. Toronto's Obsidian Theatre, Canada's professional black repertory company, is presenting The Piano Lesson as its second full production to date (after the highly lauded Adventures of a Black Girl in Search of God by local author Djanet Sears). It's only the second chance - ever - for Toronto audiences to see one of Wilson's plays professionally performed.

When she began reading Wilson's work, Barbados-born Alison Sealy-Smith, who directs the upcoming production, found herself questioning the premise that underpins Wilson's work: "He is touted as somebody who is chronicling the black tradition, and when you live in it, it's a bunch of very fragmented communities," she says. "What is it that you are all held together by?"

However, after a few readings of The Piano Lesson, "the voices changed for me," she says. "Instead of hearing the voices of Pittsburgh in the 1930s, I started hearing the voices of people I had heard in rum shops, that I had heard in family gatherings. I realized that I was part of this tradition."

Sealy-Smith says that at one time she felt rooted solely in her own particular Caribbean culture. Now, she says, she not only accepts the concept of an African ancestral legacy, but questions "Why was I trying to deny my Africanness?"

Both in the drama and in real life, "This thing about shared ancestry: it's so important to what this company Obsidian is about," Sealy-Smith maintains. "We have founding members who are from Halifax, Ottawa, Antigua, Barbados, London. There is a black tradition. There is a way of looking at life."

The Piano Lesson explores these issues particularly. Wilson set the play in 1930, when "Blacks are moving into the city. It's an attempt to transplant a rural culture into the urban north," he says. In a home in the north, one family struggles with their legacy - literally, since they have inherited a piano carved with scenes of their own history. For this piano their forebears were sold, and for its sake their father died. Whereas daughter Berniece wants to keep the piano, her brother Willie Boy has plans to sell it to further his dreams of owning property.

"Many people misunderstand the play," says Wilson. Often they assume that Berniece is the whole and healthy character, whereas, he says, she is in fact unwilling to accept her own history into her life. Not only does she forbid Willie Boy to sell the piano, but she will not play it, because she knows that it is a bridge between the living world and that of those who have gone before. "Many people misunderstand the play," says Wilson. Often they assume that Berniece is the whole and healthy character, whereas, he says, she is in fact unwilling to accept her own history into her life. Not only does she forbid Willie Boy to sell the piano, but she will not play it, because she knows that it is a bridge between the living world and that of those who have gone before.

"She has a self-imposed taboo, until her back is to the wall. Then she goes there and calls upon them. It's not a plea; it's not a supplication: it's a demand," says Wilson. "It's the question that African Americans must ask: What do you do with your legacy?" he continues. "Can you achieve a sense of self worth by denying your past? It's an affirmation of your past; that's how you achieve a sense of self worth, by embracing it. This, of course, is universal."

Eight of Wilson's projected 10 plays have already been produced, and the ninth, titled Gem of the Ocean, premieres at Chicago's Goodman Theatre on April 18, and then moves to L.A.'s Mark Taper Forum from July 31 onwards. Ma Rainey's Black Bottom has just been revived on Broadway at New York's Royale Theater in a production starring Whoopi Goldberg, along with Charles Dutton from the original cast. By chance, Wilson's final two plays in his series will cover the first and last decades of the 20th century. "I get to write the two bookends," he says. "That's simply how it turned out, an opportunity to link the two plays."

Looking back, although Wilson allows that "There's always hope," he feels that there has been "very little" progress since the beginning of the 20th century. "Obviously there have been some changes, but you still find the vast majority of black Americans living in poverty, without the tools of advancement, without access to banking capital," he says. Ironically, he points out, "We lost our economic base with the outlawing of segregation in 1954," (because community businesses often could not compete once their black customers were able to spend their money anywhere they chose). "We never got anything back for that," says Wilson.

The final instalments in Wilson's series will tell us more about the mysterious Esther, a healing woman who is discussed by characters in several of the plays, dying in King Headley II at the age of 366. In the upcoming Gem of the Ocean, says Wilson, "She's a mere 287 in 1904."

Allegory, of course. "She's a repository of the body of wisdom and tradition. She has all the memory of all those Africans who ever lived," Wilson explains. "This is very African also, where the memory and the history are kept alive, and it is the obligation and the duty of certain people to carry that along."

Certain people like griots, or playwrights.

Obsidian Theatre Company presents August Wilson's The Piano Lesson from February 7 to March 2 at the du Maurier Theatre Centre at Harbourfront Centre, with a cast that includes Yanna McIntosh, Michael Anthony Rawlings, Walter Borden, Kim Roberts and Ardon Bess, among others. For tickets, call 416-973-4000.

|

They play an especially important part in Wilson's transcendent 1990 script The Piano Lesson, which won him his second Pulitzer Prize, as well as an American Theatre Critics Award, the New York Drama Critics Circle Award and the Drama Desk Award. Toronto's Obsidian Theatre, Canada's professional black repertory company, is presenting The Piano Lesson as its second full production to date (after the highly lauded Adventures of a Black Girl in Search of God by local author Djanet Sears). It's only the second chance - ever - for Toronto audiences to see one of Wilson's plays professionally performed.

They play an especially important part in Wilson's transcendent 1990 script The Piano Lesson, which won him his second Pulitzer Prize, as well as an American Theatre Critics Award, the New York Drama Critics Circle Award and the Drama Desk Award. Toronto's Obsidian Theatre, Canada's professional black repertory company, is presenting The Piano Lesson as its second full production to date (after the highly lauded Adventures of a Black Girl in Search of God by local author Djanet Sears). It's only the second chance - ever - for Toronto audiences to see one of Wilson's plays professionally performed. "Many people misunderstand the play," says Wilson. Often they assume that Berniece is the whole and healthy character, whereas, he says, she is in fact unwilling to accept her own history into her life. Not only does she forbid Willie Boy to sell the piano, but she will not play it, because she knows that it is a bridge between the living world and that of those who have gone before.

"Many people misunderstand the play," says Wilson. Often they assume that Berniece is the whole and healthy character, whereas, he says, she is in fact unwilling to accept her own history into her life. Not only does she forbid Willie Boy to sell the piano, but she will not play it, because she knows that it is a bridge between the living world and that of those who have gone before.